![]()

The

Pioneering

Pig

by

Norman Blake

drawings by

Edward Layers

Faber and Faber

24 Russell Square London

First published in mcmlvi

by Faber and Faber Limited

24 Russell Square London W.C.I

Printed in Great Britain by

Latimer Trend & Co Ltd Plymouth

All rights reserved

by the same author:

Hayricks and Muddy Boots

(Lindsay Press)

![]()

I would like to express my thanks to Mr. L. D. Hills for reading the manuscript of this book and for making many helpful suggestions and to Mr. Harold C. Tilsey of Yeovil, for taking the photographs.

N.B.

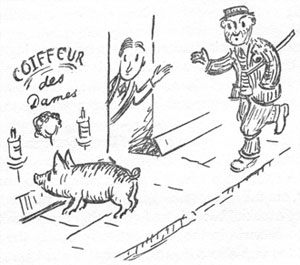

IT IS reported that Admiral Blake had the last pig in Taunton squealed at each corner of the ramparts to kid the Royalists that the town was full of pigs. We fear that the author of this book, who stems from the same family as the Admiral, would have stifled his indignation with difficulty had he been present. Pigs are to Mr. Blake what troop horses were to the old cavalry officer. For thirty years he has fed pigs, watched pigs and planned with pigs. Only recently he bought another house with fifty acres of woodland – for pigs.

This is not just another book about routine. It is an adventure story that will appeal not only to those who use pigs or plan to use them for a livelihood, but to all those who, surveying derelict land from a train, feel that something should be done about it. Mr. Blake claims that where man can make a garden, pigs can make a farm. His ideas for the use of pigs on the normal farm are equally interesting; cows are poor soil feeders and though allergic to sheep they will graze with avidity after pigs.

The Pioneering Pig is a lively and controversial book, and many who read it will be eager to experiment with the author's ideas.

Author's Note

The Pioneering Pig

Contents

Photographs

Introduction by Robert Henriques

1. I Like Pigs

2. Marginal Land and the Pig

3. Clearing and Cropping

4. Planning and Fencing

5. Housing

6. The Sow

7. Feeding

8. Managing a Pioneer Herd

9. Pioneer Pigs on a Normal Holding

10. You Like Pigs?

I. The sort of land to start on. The stalks that look like dead docks are dead docks

II. Housing. These can be carried on a buckrake. They have no floor and will accommodate ten bacon pigs. In summer they will not give cool lying

III. Housing. The old wagon may be unsightly but it gives shelter, shade and magnificent rubbing points

IV. Marginal land. The jungle

V. Marginal land. A bundle of laurels for house-making

VI. Marginal land. The demolition squad

VII. Marginal land. Woodland house

VIII. Another roofing idea suitable for the summer

IX. Feeding. Pigs fattening as they grow

X. The Sow. Winter or summer your pig should be as comfortable as this

XI. Management. A winter family, one day old

XII. The normal farm. Sows and litters get their noses into the couch (see Illustration 1)

XIII. The normal farm. Winter oats following the couch

XIV. Swedes and kale. Another first crop on derelict land

XV. The normal farm. Dry sows folding off swedes and kale

I COMMEND with fervour Mr. Norman Blake, his pigs, and the book he has written about these robust and co-operative creatures. I have learnt much from Mr. Blake on this subject and I might even regard myself as one of his converts. Not that I have ever had any doubts about pigs. I have always thought of them as nice people and a profitable farm project. But some years ago, when I first visited Mr. Blake and saw his admirable gangs of porkine contractors at work, directed by a young man in a caravan on the edge of a stunted forest, I realized that the pig can be far, far more to man than a mere friend, companion and breakfast.

Certainly Mr. Blake sends his complements of pigs to the bacon factory; but in addition, or perhaps primarily, he uses pigs to reclaim derelict land and get it into cultivation. He says: 'I am writing this book because I love pigs. They are wise and they are active; they don't wait for something to turn up – they turn it up themselves.' It is, of course, this turning-up habit which Mr. Blake exploits in his work, The Pioneering Pig.

Mr. Blake writes about his pigs with considerable humility. 'I very much doubt whether I or any other man has any right to lay down the law on pig management. We none of us come from a family of eight or ten born on the same day, reared strong and hearty to a wage-earning age. So I suggest that a safer course on deciding what the pig needs is to find out what the pig wants and supply it.' This Mr. Blake does. His knowledge of pig language is phenomenal. He knows that a pig is never ill, but is only the victim of mismanagement which it is the human duty to discover and correct. He holds moreover that, when the management is right, there is practically nothing in the world that the pig cannot do for man, from purging Soviet Russia of Communism to reforming criminals: 'The Home Office experiments with prisons without bars. In all honesty I cannot imagine a prisoner making a get-away if he had two or three sows under him due to farrow in a week, or he had just broadcast some cleared land with grass seed. Growing things is so much more exciting than picking locks. . . .'

Mr. Blake is a man who is used to very hard work, when necessary, but sees no point in it. Much of his excellent instruction is devoted to avoiding human labour, or replacing human labour with forethought and intelligence. He suggests what clothes to wear, what tools to carry about, and how to manage those tools so that they are not constantly lost. All such practical hints are given with great gusto, humour and sometimes wit.

Nevertheless the book is really quite serious. Mr. Blake honestly believes and persuades us – he persuades me at least – that not withstanding the Landrace, the pig has a nobler destiny than a Scandinavian pighouse. What that destiny should be, and how we can profit by it financially, physically and even spiritually, is the subject of this book.

Robert Henriques

Winson, 1955

I LIKE pigs. They are wise, active and thrifty; they don't wait for something to turn up; they turn it up themselves. A lot of rubbish is talked about hardiness and constitution. One sees photos of pedigree pigs ranging in the snow, a photo to prove how hardy they are. Dash it all, every T.B. sanatorium in the country works on this principle – all fresh air, warmth in the blanket and good food digested and never in the atmosphere. Pigs are neither hardy nor delicate; everything depends on how they are kept. But if they are allowed to range to find some of their food, given adequate shelter from wind and rain, and plenty of bedding to plug the holes, promote warmth and clean their coats; if they are kept in batches of approximately thirty in a pen so that they can be snug on a cold night, then you need have no fear your pigs will stand any climate that will occur in countries where grain ripens. If you choose to keep pigs in reindeer country you must write a book yourself.

The difference between the pig and the sheep or the cow is that they grow winter coats whereas the pig has a coat that is to all purposes waterproof. I should always avoid a coarse heavy-coated pig as one that had been kept in cold, dirty surroundings. This protective peculiarity makes community warmth essential.

Sacrifice your own comfortThe pig community idea is important in another field. We often read of stray dogs worrying sheep: keep your pigs in batches and you can always sleep sound on this score. Pigs will turn and fight. Try the experiment of picking up a small pig and making it squeal; the rest of the bunch will not gallop away, but will form a phalanx and advance with angry grunts, whilst the sows in an adjoining pen make it quite clear that if the squeals continue they contemplate community action. We have a cross-bred bull terrier, a wise old bitch who considers it her privilege to maintain discipline. She likes to creep up behind a half-grown pig and nip its hind leg. She can only do it once, and if she comes into that pen again that day and is spotted the whole batch join forces and turn her out. As for foxes and badgers – well, with a sow who has eight to ten piglings it is no exaggeration to say she is eight to ten times tougher than any other farm mother. One minute she is grunting sleepily and peacefully, a split second later she is at bay, hackles up and teeth bared. It would be safe to say that all four-legged vermin except rats are allergic to pigs. This is particularly the case with rabbits. Pigs grub out their young, fill up their holes and break up their hide-outs.

Dogs we love for themselves. Horses we honour and admire for their achievements. Black Beauty, who taught all the children to ride and gave them their first hunts, was bought off a gypsy for fifty-five bob [shillings]; Fearless, bought as dangerous and unbreakable, and worked for fifteen years without complaint. And there was Folly, her son, who bucked the General off when we were trying to make a sale. All individuals with their special characteristics. It is different with the pig. Two pigs in a sty are two pigs in a sty, two pigs so many weeks off bacon weight. But a pig unit of a hundred or one hundred and fifty pigs is a farm department not only providing meat, but cultivating and manuring the fields and sometimes demonstrating to the boss that what he rated as good grass was really rubbish. I have always felt that the right spirit in which to manage pigs is that of the company commander on active service. He sees to the comfort and well-being of his men and will sacrifice his own on their behalf. He does not over-coddle his men and they respect his discipline. Pigs are essentially animals that resent being driven. Shouting, running and vicious sticks are all signs of serious mismanagement.

This book, then, is for those who believe in studying stock with their heart as well as their brain. It is also written for those who want to climb the agricultural ladder from the very bottom. Few people appreciate the fact that while a calf has her first calf at two and a half years old, a pigling may at that age have bred a family of fifty, many of which will already have left for market. Fifty years ago it was a common practice for farmers to let their dairies to men of capacity with thrifty families. The dairymen paid roughly the value of the cow per year for her milk, the farmer providing grazing and hay, replacing casualties and providing facilities for the dairyman to keep pigs and poultry. The dairyman and his family minded the cows, made butter or cheese, the skim or whey being the basis of the pig-fattening project. The farmer, unhampered by milking and cow problems, could give his full attention to the cultivations, sheep, fattening cattle and his sporting activities. The dairyman plugged away year after year until death or a corn slump intervened when he often emerged from obscurity and bought the farm. Many of our best farmers stem from parents or grandparents who rented dairies.

Dairy renting as a potential ladder for the keen but poor is a thing of the past. Taking it by and large the only farmers other than market gardeners who came through the twenties and thirties were milk producers. No genuine farmer enjoys providing milk, cows are such autocrats, and farmers are autocrats themselves. But liquid sales and not cheese and butter are now the rule and milk has become respected, so that a thrifty farm worker can no longer hope to rent a dairy. He might, if he has a good mate, persuade the farmer to let him run a half-size pig unit in woodland and rough grazing. Only let him be quite sure with an agreement in writing that he is going to get full value for manurial and cultivation improvements.

Ladder is a misnomer applied agriculturally; there are too many rungs non-existent. There are no farms. Security of tenure ensures that only the very worst can be evicted, and we are all such decent fellows that we hesitate to dub a man the very worst. Besides, if we did his friends and neighbours and the vicar will write vociferously for him and against us, so why worry, we've got our farm, and if the youngsters want to farm, let them go oversea! No, there are no farms, and if there were, how can a man, because he loves the soil, which means he has worked with it for years, afford the ingoing valuation with milking machines, tractors and the simplest of implements? He can't do it, unless he is a farmer's son and can wangle some stock off his old man, and perhaps borrow his pick-up, bailer and combine. Otherwise he must be an industrialist's son, who may not love the soil but whose father loves him and thinks he ought to love the soil. If you are neither a farmer's son nor have unlimited money at your back, and you still want to farm, you must learn from the pig and turn something up yourself. Pioneer pig farming is the only way to use courage and energy and stock sense, which is another way of saying wise sympathy, to win a farm of your own in this country.

Few nice people have much money these days, so don't be worried by the fact, but get a large box and pack away every book or other treatise which recommends pig success by spending money on buildings, weighing machines, medicines and heat gadgets. Then find everything that you have about pigs in Denmark and put that in the box too: you may need two boxes. The Danes are delightful people. I studied there for six months back in '21, but are not we rather mugs so readily to take them at their own valuation? They stem from the Germans who glory in being directed from above. It is their book to emphasize their tremendous superiority all trimmed and docketed by copious statistics. I remember in '21, when I was working with the cows, the milk recorder, who was not a good early riser, arrived half-way through morning milkings, but all the returns were in order! All their stock are housed all the winter and the possibilities of open-air pig farming are as little known to them as is the use of sheep in arable farming.

Come, come, Mr. Blake, you can't get away from figures. The Danes can produce bacon at 25 per cent below our costs. Sometimes I wonder whether accountancy fever is not as dangerous to farmers as swine fever is to pigs. I remember years ago a popular daily was running a 'The Farmers are Ruined' Campaign. A friend of mine was run to ground by two sleuths with pencils and notebooks, so he swallowed twice and nobly declared that he had lost money for the last seven years. The trouble came the following Monday morning when all the old men were minding the time when Mr. Blank were a little boy running about without any seat to his trousers. Like an old nurseryman I have heard of, we are born with nothing, start on a capital of five pounds, lose money all our lives and die with thousands.

Perhaps graphs and all the paraphernalia of food costings are an essential in big-scale pig farming, but I am planning for you a one-man show where your eye and your ear and your nose will guide you and your instinct will be against any expenditure that is not food or seed. When the hard times come and the newspapers report farmers killing their suckling pigs at birth and fattening out their sows, you will be economizing by folding off your corn, and in the straw and in dung plaster left growing one of the two or three crops that still remain profitable.

Thirty years ago, on Stanley Wilkins's farm at Tiptree, I learnt that pigs, if given sufficient bedding, can be kept warm and comfortable without floor boards. That is a lesson I have never forgotten, and 1 strongly emphasize it to my readers. The reasons are economy, mobility and comfort. A wooden-floored house I have always found is pulled to pieces in a year if it is pulled about, and for this type of pig farming mobility is a prime essential. A floored house has to be made so strongly that it is bound to be expensive – well, look at the prices for yourself! A pig is an animal of curves, we all know how uncomfortable a wooden bed is, and it will be noted that the first thing a pig does when moved into an earth-floored house is to hollow out a centre. This is partly his way of reducing draught and keeping back potential floods, but since he does it in summer and in the open he must like curves to lie in.

If I was writing an ordinary book on pig keeping I should give you a list of pig breeds and recount their excellences and I should write with my tongue in my cheek. Keep what breed you fancy, I will content myself with a few main principles. Black pigs are likely to be hardier than white pigs, black is known to be a hardier colour. Pigs that are considered unsuitable for bacon because they carry too much back fat are certainly hardier than the long lean pigs, because fat is a protective tissue. More than half our pig population is required for pork, so that it should be possible to draft the short fat pigs for this and keep the lengthy pigs for bacon. Finally, over-long sows that waddle like centipedes are apt to be clumsy mothers and poor foragers. Take your choice of breeds, then, but use active sows. Get your length from your boar. I always like to buy my boar while he is still sucking, so that I can see his mother and relations. If you are worried about length and back fat, give your pigs longer to mature by restricting their diet for the last three months.

The craze of the moment is litter testing, which, if we are to believe the reports, will improve our pigs as quickly as milk recording has improved our cows, i.e. about 100 gallons in thirty years! I have always found that by and large poor litters come from poor management. In other words, under good management results will always be profitable. To pretend that by litter testing you can improve the size of the litter-milk production in the sows, the shape of the pigs and early maturity, is asking us to believe that one might breed a horse to win the Derby, haul the coai, and teach the children to ride at the weekend.

Finally, I must urge that what I have in mind is no office-wallah's Elysium. The pig does not respond to graph control and the prick of the hypodermic needle. I have written a book for men and women who have the time and desire to paddle their own canoes. This book will start them thinking; they will make mistakes and learn therefrom. Many will take a few hints and when they fail blame me. Others will open with enthusiasm, succeed, expand rapidly, and find themselves with insufficient capital to finish their pigs. For pity's sake don't take to selling small stores, the food bills may be lighter but you carry all the cares and responsibilities of breeding and rearing and, just as the pig is over his troubles and only wants two months' food, you out him for about half what you could get two months later. When the pig market begins to fall it is always the small stores that fall worst.

The bulk of the failures will occur when people try to blend my ideas with the pigsty, parlour, Danish House; call it what you will. Immediately attention is diverted from the main plan, the land is robbed of its most valuable manure contribution, and the chance of disease increases by half. Better redesign the unwanted buildings now as grain stores or deep-litter poultry houses. One man can manage a sixteen-sow unit and have time for chores morning and evening. He can probably manage twenty-five to thirty sows if he is doing nothing else, but he will find it rather a rush and he will have less time to study his pigs. If he finds success around the corner, trebles his pigs and engages a couple of men, he is heading for an early and costly failure. A pioneer project requires one man in complete control and your employees will certainly have their ideas of how they can save time and improve efficiency, and if the pigs don't do, it will be your fault. I will make one exception, I will allow you to take on a boy from school at the end of a year.

Graph control methodsThere are twenty-eight thousand square miles of marginal land in this country, much of which is suitable for pig pioneering. Is it a fact that every young man must have a council-type house, roads and everything laid on before he will consider a farm? No, of course it is not, but the trouble is that the boys who would be pioneers never have the capital to start even a pioneer pig farm. I remember once running into a depressed ex-Jap P.O.W. When he was out there he was in charge of the pig farm. He started with two half-wild sows and he finished with fifty pigs: and now he was back in England, and all the officials would allow him to keep in his new freedom was two sows, and he sighed for captivity and pigs.

Things are not as bad as that now, at any rate food is off the ration and corrugated iron and rough timber is to be had. Perhaps you would have to plan a spare-time unit of four sows on three to four acres of ground, but if you feel like pioneering – well, read on. The very idea of living one's own life and standing on one's own feet is anathema in this era of regimentation. We are all expected to fit into grooves or holes, which is probably the reason why wagon trains and stampeding herds are still such satisfying fare. Make no mistake about it, when you start pig farming you are on the high road for adventure. In fact, I once found myself with a capsized trailer and five pork pigs on the A 30 road. On one side of the road stretched Salisbury Plain, and on the other a waist-high thorn thicket ideal for pig cover, but impossible for human negotiation. My destination was a pig farm a mile ahead, for reloading; vehicles were rushing by at one a minute. Perhaps that is an exaggeration: in fact, I have always found that small pigs have a sobering and humanizing effect on all motorists. They most of them pull up and survey us with interest and envy; mothers and children become almost moist-eyed, and lorry drivers grunt: 'You can put one of those in the back if you like.' To which my stock answer is: 'You can have what you can catch'; and we chuckle at each other. In my long experience I have met only one original man. He was sitting nonchalantly in his powerful two-seater, I was on this occasion mounted. Pointing at the pigs, he inquired: 'Where is the meet this morning?'

MARGINAL land can be divided into two categories, according to whether it is trees or heathered. Without doubt you can find marginal land within fifty miles of where you are when you read this. Because you are going to start a new life with a big idea, don't imagine that the first thing is to take a long journey. The nearer you are to home the less your cost of transport and the more you'll feel at home at once with the locals. There is a danger of course, that you will find it difficult to be a pig farmer within fifty miles of the place you were a bank clerk, whilst it may be impossible to persuade your mother that your pig party is more important than her tea party. However, on the assumption that you could start quite close to home, you can have real fun finding your ground and planning your farm without spending a penny or really mean to either!

Derelict woodland is to be found all over the south of England, which I know best, particularly in the Home Counties. This is important, for the nearer you are to London the more money everything makes, which is the reason that cattle sold at Reading make more than at Yeovil, and those at Yeovil more than at Exeter. A second reason for choosing the Home Counties is that they grow city farmers, men full of enthusiasm but often managed by bailiffs and managers who trade on the boss's absence and ignorance. It should not be hard to find one of these with an area of derelict woodland, woodland from which all the saleable timber has been moved, leaving behind dead tree-tops and an abundance of brambles. Your ambition should be to rent fifty acres of such land; if it is thirty it will do, but below twenty is not enough. Your ambition is to rent this land at, we will say, 10s. per acre, with the option of purchase at an agreed figure, not more than £20 per acre or, shall we say, the value of adjacent third-class pasture. The option to extend for three to five years.

You will be wise to get clear in your mind what you want and then consult a land agent and act through him. If you know the price you are prepared to pay, and if you are prepared to rough it in the matter of your accommodation, you will be a client of great value to them, and they will serve you well. Roughly, your own accommodation is the key to the situation. A young friend of mine bought a farm five miles from a market with a two-roomed shack to live in for £10 per acre last year.

The caravan is an ideal dwelling for a young man on a pioneering job, even for a young couple with camping experience, but when the family arrives it is nothing like so good. It has several advantages in the early stages of an enterprise: it is cheap (roughly – £250 will get a new one); it can be easily sold and towed away when you can afford better accommodation; everything is compact so that housekeeping is at a minimum; you can put it where you want it, and you are clear of all the regulations relating to plans and housing standards which prevent any pioneer building a log cabin.

Clearing marginal landThere are regulations, and if you are going to have a caravan on one site longer than 60 days, altogether or spread out through the year, this site must be properly approved by the local authority. Go and see him at the Public Health Department, tell him what you are going to do and he will probably be most agreeable. What he is out to prevent is your getting a site approved and then renting caravans to other people, so that he has an eyesore colony on his hands. Satisfy him that you have a water supply and will keep the place tidy with a caravan for one (or two) while you are getting started, and you will have official approval. Do not go with the idea of meeting some damned Jack-in-Office! You will probably find an older and a wiser man than you, who appreciates an enterprise and pigs too.

Before you say: 'I couldn't sleep in a caravan', go and see some, spend a holiday week by the sea in one, and you will find that they are a great deal better than the timber and corrugated-iron shack that someone put up before there were so many regulations and now wants £500 for. Basically, the caravan cuts out the need to start by paying out £1,500 to £3,000 for house and land, and always marginal land is where there are few houses, or, as in most of the Home Counties, where they make high prices. Don't say: 'It can't be done.' With two years in a caravan it can, and on less than the price of the cheapest new car.

Caravans have another advantage, they bring a fellow bang up against his job. I was brought up on that grand adage: Never ask a man to do what you would not do yourself. Those shelters you are putting up for the pig, they are equivalent to a caravan life for him, and you in your caravan will be the more careful. Sometimes it will entail going the rounds with a torch in the rain; more often you will sleep the better for the knowledge that you will hear should anything unfortunate occur. Remember that great word TACT! If you are the tenant of A, do not pitch your caravan with adjacent and ominous sentry-box in full view of B's bathroom window. For B will undoubtedly vow, as he cuts himself shaving, to make things warm for that something pig farmer and he will be as good as his word. Snuggle yourself in under a protecting bank, show any caller the pigs and invite him in for a cup of tea. He will probably respond by inviting you to Sunday dinner. You answer that what you would really like would be a hot bath and – the British being what, thank God, they are – you will probably get a hot bath, a Sunday dinner and a valuable ally!

Roughing it may not appeal to you, but remember you are being paid for living in makeshift accommodation very highly, and tax-free. When you have reclaimed your land, you will either live on the farm you have made – in which case the increase in value will justify a loan for the house you will build – or sell. If you sell, the increase is tax-free capital gain, which is why I so stress the Home Counties, because here grassland is always saleable at a high price and, as well as your neighbours, some London wallah may be looking for a country-house site. Ask any estate agent which he would rather sell, a fifty-acre dairy holding in Surrey or in Wales!

Derelict woodland is usually to be found in an area of pretty good fertility, and when you have finished, the land will be good saleable pasture. It may slope down to a stream and, while water is always useful, you want to make sure that the land is not normally waterlogged. Pigs must have at least half their range well above water-level. Remember, also, you have to get your food to the pigs, and bedding, in all weathers, so that it is a wise precaution to have a metalled track at any rate to your gateway. It is quite incredible how ground churns up in the winter, and your neighbour and perhaps land vendor, who is quite happy to let you travel through his ground in the summer and autumn, and promises you that it will be all right in January and February, is nevertheless likely to be considerably less enthusiastic when you have had to move out of the first lot of ruts to a second trackway and are contemplating a third route.

What you will find inside the gate of your Garden of Eden will vary, but for your own sake I hope it will contain a fair proportion of blood, sweat and tears. If it does not it will probably mean that you are doing the job with hired labour, which again means that the last ten acres will take you just as long and be just as badly done as the first five, and you will learn nothing. Your land will, of course, be full of tree stumps, but probably these will be less bad than you expect. They make tracks for hauling food rather difficult to engineer. There will also be quantities of nettles to sting you, and brambles to tear your ears, face and clothes. There may be a stream that will serve you for water and give the pigs what they love in summer – a good wallow. So under all considerations I think I should recommend the beginner to go for derelict woodland as likely to yield a higher return for the labour of cleaning, especially in the Home Counties. Remember once more to have your agreement about the land in writing as soon after you start as possible. Start when the season is right, or the bank balance is satisfactory, or because it is time to get going, but make the legality of your tenure the first charge on your spare time.

The second category I mentioned was what I called heather land. This varies from hill grazing and neglected poor land to all-out moorland. I think I should leave the Government to tackle the latter for the time being at any rate, and be a bit chary yourself until you find just what the pigs will do. There is an old saying – well, perhaps it is not very old, since I invented it myself – that where man can make a garden pigs can make a farm. If your potential site has a thriving road-house just down the road with a useful kitchen garden you may, I think, proceed with more confidence. But observe the tracks and the roadside: very often you can see trefoil struggling to make a living. If trefoil and white clover are there, even in minute quantities, the land has distinct possibilities! Again, get your land on lease with an option to purchase. A word about shelter. It is important with open lands, presuming the prevailing winds (meaning the rain-bearing winds) come from the south and west, if you can get, in your holding, a good bank under the natural shelter of which pigs can feed and shelter: it will save you much winter worry. Otherwise get busy with a spade and dig your own bank, two foot high for the smallest and perhaps three foot for the stores. Dig a little and watch a lot.

Pigs can swimPerhaps 'use your eyes' describes what I want better. As well as incipient clover observe bracken. Bracken is no fool, he never pitches camp in land that is subject to winter floods, for one thing. That is worth remembering. It is very easy on a heathered moor to put up houses in summer and before winter you are six inches deep in water. In general, it may be said that the less there is to clear the less is it worth the clearing. Land that is covered with bracken and brushwood and brambles has probably three times the intrinsic value of the heath. Be shy of a large area of rushy land, the rushes mean that its water-level is much higher than it should be. It is an advantage to have land like this into which pigs can run in the summer, but do not depend on it unless, of course, your luck is better than mine! Were I to fence pigs on rushy land on a sunny summer day, we should undoubtedly have a two-inch thunderstorm that night, and I should have to face the pigs' bad language in the morning. Pigs can't swear! You wait until you've kept them as long as I have! There is one other type of land I might mention – poor cold clay. It's cold because it's poor, and it's poor because it's cold. My treatment of such land would be lime and crop in the spring with beans and oats, mainly beans, the oats in case the beans fail. I should let this crop ripen, and then turn the pigs in, to eat the corn and tread the straw into the ground, follow with wheat and harvest in the normal way; a pig will do well on that fed in ear too.

All this is very breathtaking and exciting and everyone wants to know what the pig has got which is denied to the sheep and the cow. The first answer is hot manure. It is well known that the practice with cattle is to turn them into a covered yard in winter, and when the straw is dirty put down more straw until perhaps there is four feet of packed manure under their feet. Pig manure, like horse manure on the other hand, heats, and it heats in ratio to the richness of his feeding. It stands to reason that a pregnant sow on a normal maintenance ration gives poorer, colder dung than a porker that is being pushed for market. 'That's wrong,' says the expert, 'everyone knows that all pig manure is cold.' But that is only everyone who has looked it up in a little book written by someone who has not taken the trouble to get his facts right. What is 'cold manure' anyway?

Well, a hot one has a great deal of nitrogen in it; poultry manure is the hottest of the lot with 1.66 per cent fresh, which is too something hot to use safely for most things. Cold manure is cold because most of the nitrogen is in the urine, which is often wasted. Besides, most of the protein which is the nitrogen in the cow's ration goes into the milk bucket. Horse manure has more, so they say that it is hot, which does not mean much more than seaside sunshine statistics.

Just to show that I can look things up too – and anything about organic manure takes a deal of finding – here is a little table:

Horse dung Horse urine Cow dung Cow urine Poultry droppings Pig dung Pig urine These figures are taken from Manure and Fertilizers, by the late Sir Daniel Hall, and show that pig manure is not so much cold as balanced.

The manurial production per 1,000 lb. liveweight is as follows:

Horse Cow Sheep Pig This means that pig manure as your land is going to get it is the best balanced manure of the lot; it has all the plant foods in step and plenty of them. Observe these figures and understand why leys will respond better to pig manure than to any other.

The heat is caused by an army of lively bacteria which, when they get into the soil, consume vegetable matter and turn it into fertility. All the lands I have mentioned, with the exception of cold clay, are full of vegetable matter that has stopped decaying because of a lack of bacteria to do the job. Pig and horse manure give these bacteria in the most active form. By the action of their feet the pigs also compress or, as it is often put, 'firm' the soil which excludes the air from the soil and promotes the good actions of the bacteria. Finally, a pig has a snout. Don't put the wrong value on the snout. A pig's snout is a gardening tool: some people think it is a British Restaurant, making meals out of nothing. I feel very strongly about this. When we were young, all the summer holidays, we had the run of the fruit cages, and in winter and Easter there were apples and nuts to be used. Of course, it never occurred to anyone, least of all ourselves, that we should want any less for dinner: why, then, imagine because he digs up some bracken roots or docks the pig will require less for dinner? With the exception of sows and, if you like, pigs in the last stage of fattening, all pigs should have all the food they will clear up. When he is clearing your land, he is working for you, good and hard. Any food he does not need for fuel or weight increase goes straight back to the soil as fertility. The only waste is what you spill or the rooks steal.

The smaller the pig the harder he is to fenceWe will now discuss £ s. d. After a lifetime following pigs and the land, I find it wise to be a pessimist. Bank managers are human, and in the country they know quite a bit about pigs. Don't borrow unless you must, but do not be afraid of the bank. There was a phrase of one of our 1914 vintage generals which I remember: 'Gentleman, personal reconnaissance is never wasted.' Remember that in every sphere of pig farming and go and look and think, and in this case put it as it were in reverse. Get your bank manager to come and see for himself what you are doing. This will impress him and incline you to greater care in outlay and management. The bank manager has wide discretion up to £500, and it only remains for you to be an obviously safe bet.

The minimum I can suggest that you start on is £1,500. This includes £250 for caravan or other accommodation, £250 for living expenses until the pigs begin to turn into money, and£200 for motor vehicle and trailer, preferably a Land Rover or jeep. There are three ways of starting. One is to buy freshly weaned pigs, one hundred and fifty of them, at market, keep them three months and turn them into pork. The pigs would cost you around £500, but you would only have to pay for one month's feed, the normal agricultural credit being two months, before you sold your pigs. There would be considerable disease risk in the method and it would certainly be common sense to keep back some pigs for subsequent breeding. The month's feed that would be due after two months and payable would be roughly £120.

The second method is to buy in-pig sows at market; of fifteen I suggest a couple might turn out barren, and it would be safe to discount the service dates by a month. If you bought eighteen at £25 they would cost you £50 less than your 150 suckers. Assuming you had to keep them an average of two months, this would bring the figure close on to £500. You should get 150 suckers from your sows, feeding the sows for two months would cost £67, so that the fifteen sows would have cost you £67. On the other hand, remember you are four months gone in your pig feeding, and it will take another three months before the pigs are sold. The main weakness about this method is that you are very liable to buy sows that have been drafted on account of trouble with their milk supply. I do not think this is catching, but it is certainly discouraging. Trouble at farrowing is a very likely cause of anyone giving up pigs, and a guarantee of her past activities is of little value. Buy gilts in pig if you like, but beware of sows.

i. The sort of land to start on. The stalks that look

like dead docks are dead docks

ii. Housing. These can be carried on a buckrake. They have no floor and

will accommodate ten bacon pigs. In summer they will not give cool lying

iii. Housing. The old wagon may be unsightly but it gives

shelter, shade and magnificent rubbing points

iv. Marginal land. The jungleThe third method is to buy fifteen or twenty gilts at weaning time, put them to boar yourself – by which time you will understand them thoroughly – and you can expect to have a happy trouble-free pig farm; but this means waiting twelve months for your profits. I am inclined to think that the best method is a reasonable amalgamation of the three. If one buys weaners, or slips as they are well called, warranted sound, pigs that are clearly of one litter, they are unlikely to bring disease if they are put on fresh ground with good housing. If anything goes wrong with them in the first week one is covered, and I do not think a pig will carry disease longer than that if he is living a healthy life.

Buying pigs at auction can be heady wine. The beginner will be well advised to make friends with the auctioneer and tell him his plans and requirements; then he will mingle with the crowd and make his bids unobtrusively. Personally, I rather favour pinching the auctioneer's leg! About one market a month should be attended. In-pig gilts will often be obtainable, and if some of the best gilts are kept back from the slips, the foundations of a breeding herd will soon be laid. The advantages of combining buying and a breeding policy are obvious, as one is kept up against hard facts instead of building fairy castles of one's position in a year's time. Slips should treble their value in three months, and the cost of their food will roughly be the cost of the pigs, so that with wise buying and careful feeding a good margin of profit is assured. The danger all the time is that success will engender happy-go-lucky buying, feeding and attention. Fifteen hundred pounds. I hope you will not start with less. If you have not the capital, find a part-time job and make pigs a spare-time activity, but don't try to start a full-scale show on insufficient capital. It turns adventure into penance.

SOME years ago I was visiting a pig farm on marginal land and found that, troubled by fence breaking, they had all the sows concentrated in a pen about the size of a tennis court, rain had been heavy and the sows were belly-deep in black mud. I was shocked, but the sows did not die, and I took some time to learn the lesson. Conditions that make the pig live uncomfortably are many; pigs should always be able to feed and drink on top of the ground, but by judicious moving of the feeding and drinking troughs every inch of a pen should be trodden and dunged.

This is a very important point, and it will save you pounds and pounds in implements and labour. Troughs should always be moved twice weekly and in wet weather every other day. In wet weather choose the driest spots. Roughly speaking, your pen should be big enough for one month. Never feed near the house. This will be amply trodden and manured without your help. You may find that the pigs don't dung where the feeding troughs are: in this case move your feeding troughs where the dung is thickest; a bale or two of straw around the troughs may improve matters and make the ground sweet.

However, this chapter is on clearing and cropping, and so far we have the pigs fenced in a smallish paddock and it is covered with bushes, brambles, nettles and one or two fallen trees. You and the pigs are working in partnership, it is not just a question of getting on with a job yourself, you must set the pigs to work also. The best division of labour is for the pigs to deal with the brambles, nettles and make tracks, and you can come behind and clear up the bushes and dead wood. Pigs won't work for nothing. If you leave them to their own devices, they will find a favourite foraging ground and knock hell out of it, while you do everything else alone. It is worth while finding out what they are finding in their favourite resort, and then give them something much better to make it 'pay' them to do your work.

After they have had their breakfast, which should be about a third of their ration, take a bucket of grain, allowing about one pound per pig, and throw it right in among the brambles and nettles and rubbish that you want bulldozed. Don't shoot out the bucket, but scatter it handful by handful as if you were feeding poultry. If you are working on the spot all day yourself, it would probably be wise to give the grain in two feeds. Maize and beans are the best grain to use, as they are bigger, so that the pigs hunt more keenly, but wheat, barley or oats will do the job. Next day, before you start your work, take a staff hook (a billhook on a four-foot pole, a lovely tool used for cutting hedges and arming Monmouth's rebellion, but in 1940 we got rifles, as well, from the Home Guard) and finish the pigs' job. The pig goes through everything, he will trample down the nettles but not brambles. However, what he leaves is very easily downed and he will come after you and nibble off the bramble leaves.

Two or three days after the first assault you can probably move up your feeding troughs. It will mean extra work, your carrying buckets of meal twenty or thirty yards; or, of course, you can put your meal in half-hundredweight bags and carry a bag, i.e. four bucketfuls at a time. It sounds an unpleasant job plodding through a family of twenty or thirty hungry pigs with a bag of meal. It can be a rotten job, and you may end up in the mud if you do not use your wits and begin by throwing a bucketful of corn into the forest for hunting, after which feeding will be more or less unmolested. I should make the pigs run back to fetch their water, which is at the nearest point to the road, as water weighs too heavy to warrant its strategical use. You may think I am 'crackers' over this business of moving troughs. I assure you I have seen land-reclamation schemes spoiled again and again from neglect of such simple points as these. It is one of those things that the owner-operator remembers and the hireling always forgets. Consolidation is only secondary in importance in land reclamation to fertility. The consolidation which sheep do on arable land is axiomatic, pigs are far more effective. They move much more and they dung much more. Finally, at the beginning, the pigs are virtually the only means you have of land consolidation.

So far we have chatted for about a page and helped the pigs on their job for another five, so I think it is time we did a little ourselves. One thing we had better do in the season is to keep a look out for wasps' nests. When you have found one throw a couple of pounds of corn at it and clear away. The pigs will lay it bare and in the evening you can finish it with cyanide. In point of fact the wasps' nests are most likely to be at the roots of bushes and under or adjacent to dead trees, both of which are your work. You will naturally deal with the bushes first, and when they are cleared you will be able to get at the dead-tree limbs. All foliage branches should be made into housing faggots, which I describe later (see Chapter 5, Housing). You will want them within a month as the pigs grow and it is time to move forward. Stack them in 'stooks' – don't leave them on the ground. When you have finished your faggots there will still be laurel limbs and perhaps hazel and alder. Cut out anything that is not rotten and when cut will make a three-feet-six-inches or four-feet stake reasonably straight, roughly point them and leave them ready for use. Bundles of ten tied up with binder twine are handy to carry. Pile all the dead and worthless stuff into pyramids, remarking, on the one hand, that carrying wood a distance takes time, and, on the other, that the bigger the pyramid the fewer bonfires to be started, the less ground is used and the more stable it is, because, take it from me, the pigs will love these pyramids as rubbing centres. In the winter when the wood is dry and the nights are cold you can burn your pyramids unless, as is probable, the wood is marked for domestic purposes.

If you are near a road and can either buy or hire a circular saw, spare time can be well used in logging the pyramids – there is always a ready sale for dry logs. Aim to sell by the lorry load. Be timber wise and do not log straight stuff that will make rails or stakes; if you do not want them yourself these are saleable.

What is to be done with the stumps, Mr. Blake? My answer is wait and see. First of all I should give them a good dose of corn within and around to get the pigs' noses working, then I should throw in some grass seed, a prelude to broadcasting behind the pigs. Do not be afraid that the pigs will eat the seed or root up the young grass. If you are keeping them busy and happy in front they will leave grass to grow on the stale ground they have left. The grass that will grow most readily under our cultivation is ryegrass, and the clover companion is trefoil. Both are the cheapest you can buy, so that you need not be afraid of using too much seed. Do not use any fancy broadcast machine; use a bucket and your hand, and your judgment as to quantity. Work out from a seedsman's catalogue, reducing 'umpteen' pounds to the acre to handfuls to the square perch. It would be worth getting hold of a hundredweight of lime and dumping it in a suitable spot. Take a shovel and throw it around in a patch fifteen yards square. This is roughly one-twentieth of an acre, and it will tell how the land would respond to lime at the rate of a ton an acre.

As the end of your month approaches, and you are thinking of Paddock Two, build sufficient huts at the forward end of Paddock One, to accommodate your pigs. Leave comfortable room for the pigs to feed and roam on the stale ground and fence them behind. A quarter of the area of Paddock One should be large enough. Fence forward to give the growing pigs 25 per cent larger paddock and begin the process once again. At odd moments and in between whiles consider those stumps or, better still, one or two specimens. Experiment with gunpowder and a good long fuse. Find some sort of authority, use a long fuse and work by stages. I understand that the police should be consulted – at any rate consult them. Start with a small charge and a long fuse, and don't be in a hurry. Get on friendly terms with gunpowder. I think gunpowder will give you more satisfaction than anything else I know. Winches and hoists have always been too complicated for me. It takes experience to get the best out of them. Stumping is a job you are going to do now and again, and I fear that the recommended gadget may prove obstinate and be left to rust away. One of the first things I bought to tackle brambles in summer was a liquid fire spray. It was great fun but, strange to say, it would not burn the brambles, which are full of sap, although appearing dead. While we are on the subject of fire I must relate another experience when I was sowing grass seed on newly ploughed heath. We sat in the car alongside to have lunch. I lit a pipe, gave the match a shake and threw it out of the window. Ten minutes later we heard a crackle, saw a wisp of smoke and found a patch of ground the size of a teacloth was burning. By the time we had moved the car it had doubled its size, and by the time we had moved the seed it had doubled again. We felt like naughty little boys and would have gone handcuffed to the police station like lambs. However, fortunately the land was surrounded on the vulnerable sides by tarmac main roads, and although our fire must have burnt a square mile, no one took any notice and no damage was done. The lesson has stuck, and I should advise against the use of fire to clear land. Also beware of tractors. They have a nasty habit of rearing, and if you are not slippy you may be for it. If you are slippy, your tractor is still upside-down, you have got to shut off the engine and get people to right her for you and listen to their good advice.

I have been told that the animals I should use in co-operation with the pigs are goats, which, by nibbling off the shoots, would kill the bush roots. I have a high opinion of goats, but goats sufficient to clear marginal land would be a formidable army. If I had a goat-liking wife or offspring I would give them the money to buy the goats and my blessing; but 1 think it would be a mistake to try and organize pigs and goats. If your wife ' reports your pigs out she is bound to do it nicely – it may be her goats next week. I fear Little Boy Blue would have been bluer than ever if his pigs had been in the 'taters' and his goats somewhere else in corn, twenty of them; and you wouldn't be able to see them either!

The crops that can be grown on well-'snouted' soil are various and are governed by whether the pigs will polish off the seed or the young plants if they get the chance; whether the crop is troubled by weeds and whether the pigs will eat the crop when grown. A properly-fed pig is not really much more interested in cabbages and vegetables than you and I are; they will eat them if they require green food and they will require it, but not much. Sows, of course, are a different proposition and will eat kale or roots like a cow, which is why I prefer grass seed to anything else. If our pioneer has a wife or buddy, and I hope he has, I should recommend a popular book on gardening. A garden, fifteen to twenty yards square, could then be laid out and the various crops planted in season. The care and hoeing would not be heavy and valuable information as to what would and would not grow could be obtained. Otherwise I should confine my crops to peas or spring horse beans in March or April and cereal wheat or oats for grazing at any time of the year. The rate of seeding works out at a handful to a patch of ground five yards long by one, so the beginner must guard against over-seeding for the sake of his own pocket.

After the land is completely clear it goes under normal farm cropping. That is in view of its fertility state. A pioneer does not want to burden himself with machinery; so the best policy is to get the land down to a good ley. If the owner has an agreement with the pioneer this will be all fixed ahead for him to take over. If the aim is to sell, a five-year ley sown by contract is a good bet; its cost and quality are considered in the valuation. If it looks poor, have it mown and let the mowings lie, the cheapest way of killing out mayweed and 'fattening it for market'.

There is not much more to be said about clearing and cropping. There comes a time when the grass in Paddock One is strong enough to put the dry sow on. Dry sows will do well on grass with some help; you might add some chicory to your ryegrass if you like, although I personally do not find the pigs relish it as I expected. The time that the sows first go on to your grass is the time very seriously to consider what additional stock you are going to have to eat the grass, otherwise it will engulf you. To begin with, it must be your stock. Your neighbours will expect to get the keep for next to nothing. Dry cows are the safest bet; keep off sheep unless you are an expert. Milking cows need buildings and hay and regular milkings which might interfere with your pig work. I have found that a judicious advertisement of horse keep in a suitable paper brings a lot of interest. Horses are much easier to fence than cattle and eat closer to the ground. If you want stock to eat grass and have not money to buy cattle, try letting horse keep, but have a written agreement.

Primitive conditionsI have dealt in this chapter exclusively with derelict woodland. I should handle any land exactly the same: that is to say, pig it until bare and firm, then grass seed broadcast. Graze the grass for a year or two and then from your observation of the grass plant, and how the clovers did, decide what crop to follow with. I should always recommend a crop that could, if necessary, be fed straight back to the pigs. Pigs will harvest oats, wheat, peas or beans for themselves, but barley gives coughing trouble. Potatoes are better than fodder beet because pigs can harvest them too. In conclusion, you may have cleared all the land available in the vicinity and wish to move to fresh fields. In this case, pig your ground rather heavily, spend three months clearing stumps and sow a good grass mixture in the spring of the year. I have purposely avoided discourse on suitable tractors and implements.

Your job is raising pigs. The capital that would be locked up in machines and tools is much better held in reserve for housing materials, food or troughs. Troughs are most important – plenty of them so as to preclude bullying: it is almost shocking how careless beginners are about troughs. If you have an acre or so of well-cleaned stump-free soil, and feel impelled to grow fodder beet – we all from time to time get these unreasoning urges – I should advise you to try and satisfy that 'thing' by potatoes, which will not need singling and are better harvested by pigs. The seed will cost you £5 to £10 per acre, £5 if you are content with stockfeed potatoes, which are quite satisfactory, but don't put yourself in the hands of the local merchant with a smile, or your seed will cost you £20. Potatoes are certainly easiest to grow. You get your neighbour to plough as well as he can with a light tractor and then go along with a stick or long-handled trowel and slip potatoes in, fifteen inches apart, every third furrow. This can be done at any time from mid-March to mid-June, but the first and the last fortnights are risky. When the potatoes begin to show, walk along the furrows and here and there press with the foot where the ground seems too open. If you have a few buckets of seed over, you might put in one wherever there seems to have been a dud. That all seems simple, and it is simple and well worth the cost of the seed when compared to fodder beet, which after ploughing will need the ground carefully firming with drags and roller – and on a small acreage the extremities are always too firm if the remainder is firm enough – drilling and then singling at a month to five weeks; and if this is not done well, and to time, the probability is that the whole crop will be spoilt. No, keep clear of fodder beet or you will be on the rocks and keep clear of a tractor of your own. It is shiny and has a lovely chug-chug, and one feels such a king sitting on top of it that it positively cries out to be used. I remember a young lady living some miles away who persuaded her mother to buy an Austin Seven. It must obviously be made to earn its keep, so she had the bright idea of hauling logs for firewood. My advice is use pigs until you can afford a contractor out of your profits and use a contractor until your profits warrant a tractor of your own. By then you will not need me to advise you.

Next

Back to the Small Farms Library

Community development | Rural development

City farms | Organic gardening | Composting | Small farms | Biofuel | Solar box cookers

Trees, soil and water | Seeds of the world | Appropriate technology | Project vehicles

Home | What people are saying about us | About Handmade Projects

Projects | Internet | Schools projects | Sitemap | Site Search | Donations | Contact us